Tyler Cowen has a blog series called "Markets in Everything" where he links to examples of bizarre areas of specialization for which there is a market... for example the market for coats made out of chest hair, topless paintings of Bea Arthur, etc, etc... I'd like to start my own: Bad Science in Everything. Just like market economies exist for even the strangest of goods, bad scientific research permeates all corners of human existence. Todays example: a study marked by Outside Online as STUDY: LONGER RUNS ARE EASIER. 25 runners tried to do a 200 miles race. They were tested three times along the races path for their nueromuscular fatigue and other body indicators. These results were compared to runners tested running 100 mile races and less, and lo and behold, the 200 mile runners performed better. The culprit, sleep deprivation, perhaps. This provides for great copy and has done so all over the web, from CBS News to Deadspin. It is also some bad, bad science.

Of the 25 runners, just 9 completed the race. They were only tested 3 times. Let me repeat. 25 runners. 9 finishers. Over 60 % of the runners who even though they could finish a 200 mile race could not. This subset was then compared against runners running 100 mile races, 50 miles races, and marathons. So all 9 of these runners' bodies were capable of running 200 miles, which makes them utterly unique, both for human beings and for ultra-marathoners. To compare them to runners running a considerably smaller distance implies that anyone who is capable of running a marathon, or even a 100 mile race is capable of running a 200 mile race, which clearly is not the case, even for those who train for it. So here we have 9 highly specialized data points which are probably not even useful for comparison to other long-distance runners. Yet they are also being used to make an inference about the other 7 billion human beings. I think I could probably run a marathon after a few months of training, but I would be utterly wrecked. To say that if (and I couldn't) I ran 200 miles I'd be feeling better? Thats some bad science. You might argue that this isn't the implication of the study, that the point is that ultra-hyper-marathoners have special fatigue properties of their neuromuscular system. This is probably true. Yet it is certainly what is being inferred in the press. Bad science in everything. Tyler Cowen, fresh off a totally seperate piece but interesting (and provocative) piece on the feasibility of sustained rapid growth in an emerging markets, brings up what he is calling "One of the most popular intellectual fallacies ever" the inability to seperate status and influence in debate. Cowen's fallacy involves the inability to seperate:

"Cowen's Fallacy" might be packed into the following: Influence is independent of discussion of influence. I.e. what we do is independent of whether people see us do it or how those people see us. Of course one's influence is tied tightly to one's ability to reach others, so I don't think independent is the right word. Perhaps a better way of putting it is: A person's influence is bimodal: a fast mode associated with effectual influence, and a slow mode associated with the response of society to that effectual influence. Which may not be easy enough to say, but allows for the possibility that there is no fallacy at all in mixing status and influence.

What do Harald Bluetooth, Luciano Pavarotti, and Niles Foster all have in common?

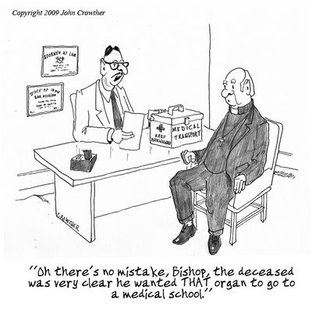

I got in a long discussion the other day about why people will choose to be organ donors. In a vacuum of social behavior, the basic act of donating ones organs after death has no impact on the person doing the donating. After all, they don't have any claim to the organs anymore and any good the organs can do will not bother them... they are dead after all. Therefore in the social vacuum, the case can be made that organ donation wouldn't survive much as a practice, as there is no real good "reason" to do it. If there was any slight pressure to keep ones organs intact after death (say a religious preference, etc.), then likely there would be no organ donors. So the question became, then, why do people donate their organs? What is it that encourages people to break this ambivalence towards what happens to the world after death? The easy answer is "a desire for their progeny to benefit from the medical progress their organs can help further". This is a cheap, 'evolution trumps all' type answer, and may be the right one. Those who are genetically predisposed to use all means to further their progeny will see their genes propagated further. And it is likely that the diseases you have that you may contribute to curing will be those of your kin, so your impact of donation is maximized amongst those who share your genes.  The problem is, organ donation is not assumed (both popularly and in fact) to be benefiting people close to you... rather it is generally seen as a societal benefit, you are doing some good for people who are ill, weak, etc, etc. and not those near to you (people near to you are the ones who are more likely to dislike the idea of your body being "mutilated" post-mortem. In the light of this fact, I think it is best to consider a "contractarian" point of view. In brief, the reason I agree to donate my body to science is selfish and societally driven. If another person dies, and their body can benefit me if it goes to scientific research, this is good for me. I like it when other people agree to donate their bodies to science! So I pressure them to do so. In return, I submit to the pressure that they levy on me to benefit their lives. I hope, in the bargain, that enough people die before I do to prolong myself. And so we sign what is, in a sense, a social contract to donate our bodies to science. What the hell does this have to do with climate science (and a host of other topics)? Consider the possibility that organ donation is a known science, but there is some reason that we will never experience the positive outcome of anyone livings organs. For example, suppose there was some scientific reason that organs, once obtained from a dead body, must wait in seclusion for 100 years before they matter to me. Encouraging other people to donate their organs won't benefit me, I'll never reap the rewards. If people in the past donated their organs, this is also no encouragement for selfish me to donate my organs upon death, because I can't enroll myself in a mutually beneficial social contract. It would seem in this framework that organ donation would die out as a practice.

This is extremely strongly evidenced in climate change mitigation. We have no real method of having our actions altering the climate we will experience, and it is therefore hard to engage in a social (or real) contract in which parties will agree to limit their emissions, even when there is clear evidence that doing so is necessary to limit the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions. It seems the contractarians have it. Alex Tabarrok at Marginal Revolution has a more nuanced take on the SCOTUS decision from yesterday: You might think that the law draws a bright line between discoveries which cannot be patented and inventions which can but that’s not correct. Discoveries can be patented and the ruling goes out of its way to push back against the view that they can’t. The ruling correctly notes that a “considerable danger” is that patents on basic ideas and tools would “inhibit future innovation”. Yet the law makes no mention of these considerations and the court provides no guidance on implementation. Its important to look on the different conceptions of "discovery" here. The way I see it, there are two types of discovery:

The metaphysical discoveries (say what you want about Platonic ideals) do not exist on their own. They exist only as a byproduct of careful thought, and are essentially developed ideas and frameworks for forming ideas. Many of the metaphysical "discoveries" made by humans over the previous thousands of years have been lost to current science, mostly because they are of no real use to humanity and do not relate to any new physical discovery. Take a silly example: Fred discovers a new novel way of making fried cups of onion. In two years it may be forgotten, and nobody but Fred may ever rediscover the method. If Fred has his memory wiped Men-in-Black style, he'll be able to find out what an onion is, even if he can't fry them just so. It is clear to me that physical discoveries should not be patentable, since there is nothing special about them once found. To patent something which you cannot exercise any true ownership over is impossible (there is much to say here about piracy and software patents). But there are real concerns about the discovery of ideas: the construction of a new model train should be patentable, because this is a developed strategy, wholly constructed and unique to its creator. But should the proof of the Lonely Runner Conjecture be patentable? What if it is a constructivist proof (though it can't be :) )? In my view, something which is patentable should be so because it at minimum involves the genesis of something. Which is why I think Tabarrok has it all wrong when he says: The ruling, for example, says that a firm can’t patent a gene that it discovers but it can patent the cDNA that it develops. It’s the discovery, however, that’s expensive. The development of cDNA is today a trivial step. Thus, you can patent the trivial step but not the giant leap. While we have made a "giant leap" forward in our understanding the world, we didn't create anything new when BRCA was found, merely observed the gene. There has been no giant leap forward in the world, just in what we as humanity know about it. The fact that a gene codes for proteins which act out some role in human biology is true whether we know it or not. So which it may seem less of a leap to understand the development of cDNA for BRCA, it is the only actual "leap" (as it applies to metaphysical discovery) here.

“I am unable to affirm those details on my own knowledge or even my own belief,” - Antonin Scalia. It wouldn't make much sense for a climate scientist to have patented geostrophy. Or Tombaugh to be able to patent Pluto. After all, these not novel, nonobvious and useful techniques or inventions, but rather "obvious" statements of facts or observation. So it doesn't come as any surprise that the Supreme Court came out 9-0 today denying Myriad Genetics the right to patent the human genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. The genes, which can cause breast cancer, are: a product of nature and not patent eligible merely because [they have] been isolated - And as such ineligible for being patented, though the technique of isolating them is.

What is most surprising is the first quote, that by Antonin Scalia, who published his own opinion (still denying MG's patent rights). It refers to section I-A of the 8 justices' opinion, which outlines the basics of molecular biology, namely:

The four major statements are points of scientific fact, and can be observed and implemented readily, even by people with absolutely no scientific training. They are confusing and difficult concepts to learn, and this is why there is nothing wrong with Scalia admitting that, even though through oral argument he had these concepts explained to him, he is know fully aware and understanding of them. This covers the knowledge part of his statement. It doesn't cover belief. It is patently obvious that these things are true, and has been obvious for nearly a half-century. For Scalia to admit his ignorance of genetics and molecular biology is fine; he represents there a majority of the world's population including myself. The real problem here is that he seems to believe his ignorance is not ignorance: he doesn't understand because he doesn't believe in the science to begin with. Again, there is no such thing as belief in facts, especially ones which we can see with our own eyes. Scalia's ignorance is two-fold, the forgivable ignorance of fact, but the less forgivable ignorance of principle. There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics. - Mark Twain People are more likely to answer factual questions incorrectly if the facts do not conform to their political biases, even if presented with news stories disconfirming their preferred belief. With money on the line, however, they will. The consequences for climate policy here are rather broad. Wonkblog writes up the a reading of a recent paper by Larry Bartels at Princeton, who showed that Democrats were: Much less likely than Republicans to correctly answer questions about whether inflation went down under President Ronald Reagan (it did) and whether unemployment also fell (it did): A second group of researchers found: Republicans presented with news articles pointing out that there were no WMDs in Iraq were more likely to say that such weapons were found than Republicans who didn’t read those articles. The implication here is that people with strong political beliefs are willing to register their political belief in a survey even at the expense of disconfirming an actual fact, which recalls the beautiful quote by Twain (which he claimed originated in Benjamin Disraeli) Yet when told that incorrect answers would be penalized by monetary fine, and by including the category "I Don't Know" as a response indicating a sort of "conscientious objection") the partisan gap (remember, this is the spread in answers on a fact based on political affiliation) dropped by 80%.  The two main takeaways here?

This calls into question reports on the acceptance of climate change in the United States: including the results from this Gallup poll. Gallup shows a major conservative bias towards a belief that climate change is exaggerated, and a liberal bias of similar magnitude (relative to the mean) towards a belief that it is not. Being that the "controversy" over climate change has become such a trenchant partisan issue, and that there is no magic information transmitted to Democrats that Republicans can't access, could it be that people are simply registering their political or religious belief into a survey, rather than their ignorance? Here's an interesting video from the "Smarter Every Day" youtube channel, a channel dedicated to showing some pretty cool, easy to understand science aimed at the layperson. The hypothesis here is that caterpillars have evolved a group locomotion technique in order to move at greater speed. While I think that the idea is pretty cool, and the explanation wonderful, I've got a bone to pick. But first, the video. Catch the idea? Caterpillars, by working together, may have been able to create a way in which a group of caterpillars can move faster than any individual caterpillar (a point very eloquently made using legos). Here's the problem. Caterpillars, like most billion-year-old species, have evolved musculoskeletal systems in response to certain selective evolutionary pressures. One of these relates to their flight response, and the muscles they have evolved to propel themselves forward as rapidly as possible. In simple terms, a caterpillar on its own is capable of moving forward at one caterpillar-speed (1 cats), moving a mass of one caterpillar-mass (1 catm). This requires the caterpillar to impart unit momentum (1 catm-cats) to itself by rubbing off of the ground. If, now, the caterpillar is required to support the weight of a second caterpillar atop its back, it is still only capable of producing this same 1 catm-cats of momentum in a small amount of time. The mounted caterpillar, assuming it can still move unencumbered, also imparts the same momentum, and so moves at speed one with respect to the poor caterpillar it lies atop. Therefore since the mass of the two caterpillars is 2 catm, the speed at which the bottom caterpillar can move is just 1/2 cats! Causing the upper caterpillar to move at speed 1.5 cats, and the average of the two to move only at the same unit speed. Aside: Why wouldn't is be possible that caterpillars could actually exert more energy, keeping themselves, even when laden down at unit speed? Why would it! If they could exert more energy, this would be of benefit to them in running away themselves, increasing the value of one caterpillar-speed, but not changing the group locomotion. Also, this extra energy would need to be expended, and the caterpillars could tire out soon after joining the group. This seems to be related to the phenomenon of group and phase velocity. The group velocity of a packet of waves is the speed at which energy is transferred. The phase velocity is the speed at which individual crests in the packet of waves move. In the video below, you can see as ripples are created on the surface of a lake. Small wave crests move fast inside the growing outer ring of the ripple. These small waves have a greater phase velocity than the group velocity! In the case of caterpillars, the "energy" is the location of the center of mass of the pile and the individual crests are the caterpillars. While an individual caterpillar may find themselves handily brought forth to the front of the pile, they will eventually be returned to the slow, plodding bottom, supporting the weight of the whole group.

Obviously, my concerns need to be falsifiable. So here are two tests of the main assumptions I make: 1: Do caterpillars on the bottom of the pile move slower than caterpillars on the top? And by how much? 2: Would a caterpillar on its own beat the big group in a race? 3: Do these large configurations persist for a long time, or are they short lived? How does that timescale relate to the periods for which a caterpillar can move on its own? The second part of this will address a few considerations as to the reason this cannot happen, as well as an explanation for exactly why it is this behavior (because it does exist, after all) is useful. |

AuthorOceanographer, Mathemagician, and Interested Party Archives

March 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed