A secondary part of the USCG Healy’s mission was enacted just a few days ago, when we diverted our scientific activities in the northern Chukchi Sea to go rescue a trapped sailboat. This sailboat, the Altan Girl,had managed to make it about 50 statute miles north of Barrow, AK before it became stuck. Us on the science side (and the bored side) didn't take long to find the blog maintained by the captain (and only passenger), is a Turkish-Canadian citizen attempting to sail the Northwest Passage in a self-built aluminum sailboat. While it contained no clues about his whereabouts , rumors flew, largely surrounding the nature of his existence, intelligence, and Soviet spy leanings. Most turned out to be false. Regardless, the sailboat had drifted over 12 miles into the pack ice. On the 7th day, still unable to move, Healy diverted our mission for the 250 mile, 20 hour trek through the pack ice to Barrow. The most interesting part of the entire experience (for us, in our warm and comfortable ship, “prevented” from working due to the urgency of the mission) was the speed. According to the pamphlets scattered throughout the ship, Healy is designed to “break 4.5 feet of ice at 3 knots, continuously”. Divide the 250 miles by the roughly 20 hours it took to get to him, and you’ll see why running through 5-6 feet of pack ice at 11 knots was so fun. An icebreaker going through ice sounds a little like an airplane going through extreme turbulence, and the feeling on board is the same (though no ups and downs, of course). The mess hall on Healy is at the bow and the outboard side, so you can hear and feel the massive chunks of ice being crushed and hurtling past your head just only a few feet away. Pushing it like this caused the cycloconverters, which transmit power to the engines, to break down about once every two hours, necessitating a full stop, 20-30 minutes of repair, and then a rapid acceleration back up to our cruising speed.

6 hours later, we reached the open water, the Coast Guard boarded and examined the ship, and the Altan Girl was set free to Barrow, complete with an official Healy hat and a bag of apples. The cost of this excursion (fuel, salary, maintenance costs) are borne by the person who is paying for the ship time, so Science was a bit unhappy for the material cost and lack of science getting done. The captain of the Altan girl, though, couldn’t have been more pleased.

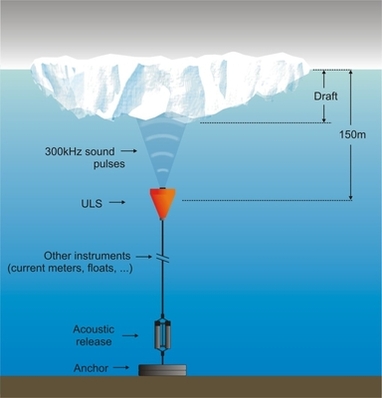

Healy's CTD and rosette Healy's CTD and rosette The most prominent feature on the measurement platform is usually not the CTD itself but an array of Niskin bottles, called a rosette. These bottles are open to the water and flood as they descend to the ocean floor, but they seal themselves when remotely triggered to at specified depths. When they return to the surface, the water locked inside is sampled for all sorts of things; nutrients, phytoplankton content, trace minerals, and so on, by the scientist on board. Also attached to the CTD are sensors which gauge transmissivity, dissolved oxygen, and fluorescence. My job on the Healy is to be the faithful recorder of the CTD’s journey to the bottom, directing it to the ocean floor, and bringing it back up (with the help of the Coasties and others doing the hard stuff like manning the winch) while tripping bottles to sample water at depth. At the surface, I sample water from the Niskin bottles, process the data obtained during the cast, and reset the measurement platform for the next cast. On a good day, we can do a CTD cast once every 45 minutes, but in ice (like we are in now), it can take over 2 hours. None of this matters, of course, if the boat isn't stopping to take measurements. As befits a Coast Guard vessel, we're somewhere en route to Barrow, AK, 200 miles through the ice, to rescue a Turkish man who thought it would be a good idea to attempt the Northwest passage in an aluminum sailboat in June. No work for me!  There are plenty of interesting things about Dutch Harbor, AK (The Deadliest Catch, bloodiest WWII battle in the U.S, most remote Safeway grocery store, etc, etc)... you can't be here for 10 minutes without being confronted by these guys. That's right: Dutch Harbor has bald eagles the way Milan has pigeons. And they aren't just friendly birds, they've been known to attack innocent Post Office patrons. Apparently this has something to do with the fact that Alaska has an endemic population, enough so that back in the early 1900's the Alaskan government paid hunters to kill the birds. During the height of DDT use, bald eagles were nearly eliminated from the lower 48, though remained in Alaska. In places like Dutch Harbor, they are on the top of the food chain, and, much like their dopier friends the seagull, hang out and eat the catch brought in on fishing boats. For a local's perspective on the bald eagle's, see unalaska from my point of view  With 24 blog posts in some stage of drafting but not published since my last one in 2013, 2014 has obviously been a banner year for "Chris Horvat's Blog". Hopefully the coming months will reinvigorate my once-unfettered interest in completion. From July 3-30, I'll be a member of the science team aboard the USCGC Healy (above), on research mission HLY1402. My participation will be in support of (and owed to the generosity of) Dr. Bob Pickart. (that's him on the right). This mission will support our understanding of the interaction of waters spanning continental shelves... but that's a very different post. Our mission will take us from Unalaska, AK through the Bering Strait and out into the Beaufort Sea. Needless to say, as a sea ice researcher I'm a bit excited. Currently I'm in Anchorage, AK, waiting for my flight tomorrow to Dutch Harbor, of "Deadliest Catch" fame. The title of this cruise is "Mooring Deployment", which means that the broad goal of the mission is, well, to deploy moorings, long buoyed cables fixed to the seafloor. These contain arrays of measurement devices which measure water properties like temperature, salinity, velocity, and sometimes chemical properties.  Generally, a mooring has four components parts:

Most moorings are also fitted with an "acoustic release" mechanism: since they move and sway with the ocean currents, it isn't clear exactly where a mooring is. So when scientists want to retrieve data captured by the mooring, they cruise around it and send an acoustic pulse into the deep. Upon hearing this coded message, a clasp at the base of the mooring releases the cable and float from the anchor, and the mooring bobs to the surface to be recaptured. On the left is an example of one typical types of mooring which is deployed in ice-covered regions. Did I mention we'll be in ice-covered regions? Most Arctic mooring work is done when there is no ice, since when moorings are deployed ice can close in on mooring lines and snap them. Unluckily for the science party (but happily for me), we have to do this mission in July, when there will still be sea ice in the Bering Strait and Alaskan Arctic! |

AuthorOceanographer, Mathemagician, and Interested Party Archives

March 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed