|

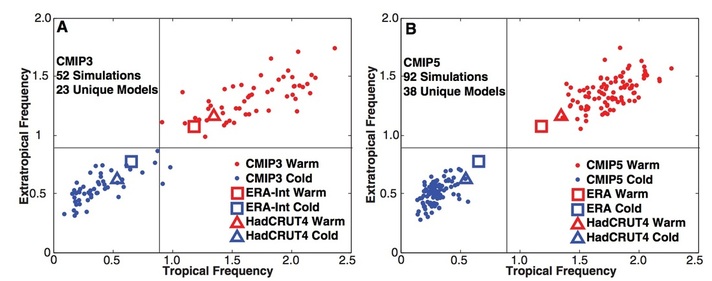

The most interesting short paper I have read in the past few years is the pre-press article by mathematician Kyle Swanson: "Emerging selection bias in large-scale climate change simulations" (behind the Wiley paywall). In it, Swanson shows that the ensemble of models most popularly used for scientists exhibit a selection bias towards accurately capturing some phenomena (say the Arctic sea ice extent). In turn, this has resulted in (for other important phenomena) an intra-model spread which has decreased through the multi-year model refinement process, but whose mean has shifted further away from reality. In other words, there is a selection pressure on climate models which seems to be guiding them to converge upon the same result... in the words of evolutionary biology, researchers belief that they are "getting something right" is what is paying for these evolutionary changes. Yet according to Swanson (and a privately held belief of many other researchers) this satisfaction is misplaced. In the paper, Swanson retells Feynman's story of what happened after Robert Milikan miscalculated the charge on the electron. When they got a number that was too high above Millikan’s, they thought something must be wrong–and they would look for and find a reason why something might be wrong. When they got a number close to Millikan’s value they didn’t look so hard. And so they eliminated the numbers that were too far off, and did other things like that (Just to establish a baseline for this criticism, this selection bias is related to model-predicted or model-diagnosed patterns, and cannot be used to criticize climate change as a scientific fact. That the world is warming has been observed, evidenced analytically, and demonstrated in models over a wide range of complexities. Enough about that.)  The picture is a figure from his paper, showing how the model spread of the frequency of anomalously warm and cold months changes from the CMIP3 (~2007) and CMIP5 (~2010) intercomparison projects. This is plotted against "observations" from the reanalysis products HadCRUT and ER. The trend is obvious: the models tend to get cluster together but their mean does not shift towards the actual data. For a long time, the rub on climate models was that they had very low precision, model spreads were large and uncertainties were high. The unmentioned benefit for this was in accuracy: real data often fell within error bars of prediction. Now we have increased model precision at the expense of accuracy, and in the hierarchy of model outcomes, accuracy should be placed above precision. Better to be reasonably sure than to be confidently wrong. This is troubling: the implication being that modellers are providing a selection pressure for results which is (in a second sense) "unnatural", and climate models are becoming increasingly covariant (perhaps in response to "improvements" in physical parameterizations that are added to the entire ensemble), but are not becoming more skillfull. Not unlike the cartoon rabbit who puts his finger in the dike, only to see a new leak spring forth somewhere else, the rush to improve climate models in certain areas has resulted in even larger problem. Hajo Eicken outlines in a recent public-consumption Nature article the rationale for (and problems with) modelling ice well, though stops short of mentioning the Floe Size Distribution! Someday...

Playing around a bit with the Google Timelapse project (sponsored by Time magazine, I guess?).

Some notes/concerns: 1: It isn't clear when these "snapshots" are taken in time. For example, the 1984 shot of Mendenhall clacier is probably taken in Northern Hemisphere winter (a guess based on snowfall over Glacier National Park). So is the 1989 and most of the late 90's images. Whether the final snapshot's indications of climate change are actually so dramatic, and not the cause of aliasing by comparing two different places in the seasonal cycle isn't clear. This needs to be corrected. 2: Smoothing is playing a big role in producing the image. Of course it takes a lot of passes to create an image of the globe, so this is necessary. But just look at what happens in the Atlas mountains between 1988 and 2003. LANDSAT catches the mountains in a time where they are ice-capped in 1998 , but it doesn't in the following years. The result is an unphysical, linear interpolation between that snowy year and the snow-free years that looks a little weird. Additionally, that question of timing I raised about Alaska glaciers is different around the Rocky mountains, by watching Lake Tahoe cover with ice we can infer that the first few years in Colorado were summertime, the remaining were taken in the winter. We need timestamps! 3: Chinese growth happens fast! Search for Fengdu, for example, and watch an empty grassland turn into a huge city between 2000-2005. You can pretty much pick any place along the Yangtze River and watch massive growth occur in the early 2000's until today. 4: Speaking of China, check out the Three Gorges Dam! You can watch as huge regions upstream are flooded as a result of its opening in 2006. Kind of sweet. “Scientific discovery is not valuable unless it has commercial value” This is a statement by the head of the largest scientific agency in Canada. No, that is not a joke, an Onion article, or an impostor. The man (John McDougall) who said this is in charge of overseeing all scientific research in Canada, giving a speech in which he outlined the new goal of the National Research Council (budget $900m): supporting only that research that is "commercially viable".

The utter myopia that led to the support, crafting, and passing of this kind of legislation by the ruling party in Canada, a by-all-accounts democratic, 21st century, forward-thinking nation, is hard to conceive of... an accomplishment that damns Canada to a future lagging far behind all other modern nation in the progression of scientific accomplishments and ideas. It also can be seen as the extension of the policies recently insinuated at by a Congressional committee member aimed at overseeing our largest funding agency, the NSF (budget $7bn), though considerably more restrictive. (A short discussion here). It should not come as any surprise, then, to find that publication under NRC-funded research grants funded in the two years since McDougall took over has dropped by almost 75%. Canada was the birthplace and home of John Charles Fields, a mathematician for whom the Fields Medal, the single most prestigious (and difficult) award to obtain in the realm of mathematics and science, is named. Now mathematicians like Fields, Samuel Beatty, W.H. Metzler, and many others, who were born, worked, and died in Canada, are at risk of seeing mathematical inquiry snuffed out in the country. Mathematics is often seen as a fruitless science, with no point and no relevance to everyday life. It is certainly the STEM discipline with the least "commercial value" to a politician. This of course, is as far from the truth as is possible. Bad Astronomy writes about the awful consequences this law may have in some detail, bringing up the case of J.C. Maxwell, discoverer of the laws of electricity and magnetism, without whose understanding we would be unable to send emails, use GPS devices, or drive cars. It is important to remind people in times like these about how science and business actually work. One more example: the semiconductor. The fundaments of the semiconductor were identified and analysed first through mathematical and physical research, starting with the Hall effect and the discovery of the electron, in the late 19th century. The idea of quantum tunneling was suggested in the early 20th century by physicists and mathematicians attempting to uncover fundamental laws of the universe. It wasn't until nearly a century later that Microsoft, Apple, and IBM relied upon these essentially pro-bono discoveries to become the world's largest corporations. Commercial viability, indeed. The NRC's phone number is 613-993-9101 New Republic has a great story on the Georgian (not the state, the Republic Of) War on Drugs. Subutex, a methadone replacement aimed at weaning heroin addicts off of needle drugs, became a less regulated and more problematic issue than the one it attempted to replace. Not only is this a case study in drug policy, but provides the opportunity for the tour de force line: Russian addicts pioneered the use of krokodil, and from there, the devil went down to Georgia.  (Krokodil, chemical name desomorphine, is the cocktail of toilet cleaner and codeine notorious for its life expectancy of less than three years after a junkie's first use, and another story of desperation in itself. ) So what is a post-Soviet country to do? Enact incredibly intrusive drug reforms. And they worked! Georgian police are legally allowed to stop any person on the street and force them to pee in a cup. Prison enrollment tripled after the enaction of these laws in 2004 (from ~80,000 to ~250,000). Nearly one in every 20 men above the age of 18 was stopped every year in the Republic during this period, of which less than a third passed dirty urine. The number of Subutex addicts in the Republic of Georgia is now effectively zero. And yet in the meantime, The United State of Georgia operates a prison program with a slightly smaller number of state inmates than existed at the peak in the Republic (210,000 versus 250,000), with a total cost of around $1bn per year. The nominal GDP of the Republic of Georgia is $14bn. The State is twice as large in population, twice as large in area, with a gdp of $400bn. So what can we infer from this? Drug reform and its consequences may be something like a multiple-equilibrium system with hysteresis. A central idea behind hysteresis is that there exist multiple states of a system which are stable at the same time, meaning trying to get away from them is difficult. Eventually, one will become unstable, and the system will move from it to the other state. A convenient way of thinking about this is a ball which lies in a system with two local minima. Both are stable in that small pushes on the ball keep it where it is. But if we increase, say, the wind blowing from left to right, eventually the wind will blow the ball into the rightmost well. Then if we bring the wind slowly back down to where it was before, the ball won't return to the original state. Hysteresis generally refers to the idea that a system has a memory. What could this say about the War on Drugs? Imagine that there are two equilibrium states:

We may never be able to escape this equilibrium addiction/incarceration problem until we reach a critical enforcement strength, far beyond what is Constitutionally permitted. What a problem! Awesome post over on The Big Questions by Steven Landsburg about polynomial equations and correspondences (just isomorphisms) between trees and n-tuples of trees.

There is a isomorphism between, for example, seven-tuples of trees and one-tuples, but not between single trees and pairs, or singles and triples, etc, etc. Amazingly, it sort of turns out that by thinking of the class of one tree as a variable, writing a polynomial equation using the same variable and solving for its root, you can create some algebraic equations that provide the results of these theorems. Weird!, and definitely worth a read. Bottom line, at the end of the day, we want our kids to be exposed to the best facts... I’ve got no problem if a local school board, says we want to teach our kids about creationism ... some people, have these beliefs as well. - Bobby Jindal That is a quote from the current Governor of Louisiana, Bobby Jindal, who manages to make explicit his internal struggle with the meaning of the word fact and belief, in defense of the Louisiana Science Education Act, which promotes the teaching of creationism alongside evolution in public schools. This would all be an interesting, teachable moment à la Marco Rubio's confusion about the age of Earth, if not for the fact that Jindal has this bill appear on his desk in 2008, and he signed it.

Unfortunately for the governate, this has not only cost students and teachers valuable time spent learning non-science, but is also costing the state some millions of dollars in revenue. Most of this loss is in the form of reduced tourism and conference fees for scientific meetings. Dollar values are hard to find, but at least one organization, the Society for Integrative and Competitive Biology, moved its 2011 conference from New Orleans in response, part of a boycott of Louisiana cities by a number of biological societies. The cost figures to New Orleans proper were released in December 2012... total loss $2.7 million. The parish of New Orleans swiftly banned the teaching of creationism from public schools just before Christmas, and the boycott was lifted. Money talks, but the boycott goes on for other Louisiana cities. Re-discovered an "old" FT piece about the problematic role cash played in fueling the U.S. financial crisis of 2011-onward. For those of us who don't hold this kind of money, for a time, Bank NY Mellon was charging customers .35% interest on deposits worth over $50 million. Why? Because the decrease in growth of the GDP resulted in what should have been a negative nominal interest rate (according to the Taylor Principle). With federal T-bonds returning no interest, and an astronomical amount of cash being held in banks (nearly 2 trillion in December 2011, relative to a typical (90's era) balance in the hundreds of billions), there became no way to generate returns on large cash deposits. This becomes a problem because, as Izabella Kaminska put it: Money has to be put to work, or else the system breaks down. Cash wasn't circulating, money wasn't being put to work, and this compounded the liquidity trap that was the late 2000's economic crisis. Money the Fed put into the system had no effect on interest rates or economic growth.

Why is this relevant today? Because one possible way out of the trap is a tax on large deposits, something that Cyprus recently announced they would commence to great consternation around the European Union, particularly because the minimum dollar value for this added tax was in the $100,000 range. Why the frustration? Just as if one were to own a few houses, there is an associated expense for physical upkeep. There is now becoming a cost of "asset upkeep" associated with the presence of large sums of cash. Though a bit surprising (we are taking on bank debt with our deposits, after all), this may be a relatively efficient way out of a liquidity trap, especially in a national economy (like the case of Cyprus) where the central bank (E.U.) isn't always playing to national interests. Based on my review of NSF-funded studies, I have concerns regarding some grants approved by the Foundation and how closely they adhere to NSF's "intellectual merit" guideline. - Lamar Smith In recent weeks Lamar Smith, the Christian Scientist chairman of the House committee on Science, Space, and Technology, has made overtures about changing the guidelines for NSF funding. Alongside his effort is the famed creator of the "Coburn Omnibus", Sen. Tom Coburn, who recently appended to the Ongoing Appropriations Bill an amendment which asks that the NSF avoid funding political science research unless it can be demonstrated that it: "promot[es] national security or the economic interests of the United States." A major push for fiscally conservative Republican lawmakers has typically been to limit the spending of federal resources on "pet projects", the so-called "pork-barrel spending" which was a major issue during the 2008 presidential election. While the amount of effort expended on this front waxes and wanes with the political cycle, it is rare that this extends to the realm of scientific research. To be sure, political oversight over grant proposals is a dangerous game. Already there exists a bureaucracy designed to establish the merits of scientific work (the NSF), which is "staffed" by scientists and researchers, not politicians with shaky scientific understanding, bent to the whim of political favor and the election cycle. There are holes in peer review at times. Cora Marret, who is the head of the NSF, admitted as much. This still begs the question: What is the meaning of peer review when the peer (Smith) is a lawyer? Or an obstetrician (Coburn)? Or any politician, for that matter? In a Nature correspondence which fortuitously came out this week, Thomas Decoursey discussed the role that politically unimportant research has on society: ... big problems faced by humankind ... can be solved only by science and technology, irrespective of profit motives. Presumably "profit" can be extended to include "national defense" and "health" as well. The dissenting viewpoint (which prompted Decoursey's argument) is worth reading as well.

|

AuthorOceanographer, Mathemagician, and Interested Party Archives

March 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed