I got in a long discussion the other day about why people will choose to be organ donors. In a vacuum of social behavior, the basic act of donating ones organs after death has no impact on the person doing the donating. After all, they don't have any claim to the organs anymore and any good the organs can do will not bother them... they are dead after all. Therefore in the social vacuum, the case can be made that organ donation wouldn't survive much as a practice, as there is no real good "reason" to do it. If there was any slight pressure to keep ones organs intact after death (say a religious preference, etc.), then likely there would be no organ donors. So the question became, then, why do people donate their organs? What is it that encourages people to break this ambivalence towards what happens to the world after death? The easy answer is "a desire for their progeny to benefit from the medical progress their organs can help further". This is a cheap, 'evolution trumps all' type answer, and may be the right one. Those who are genetically predisposed to use all means to further their progeny will see their genes propagated further. And it is likely that the diseases you have that you may contribute to curing will be those of your kin, so your impact of donation is maximized amongst those who share your genes.  The problem is, organ donation is not assumed (both popularly and in fact) to be benefiting people close to you... rather it is generally seen as a societal benefit, you are doing some good for people who are ill, weak, etc, etc. and not those near to you (people near to you are the ones who are more likely to dislike the idea of your body being "mutilated" post-mortem. In the light of this fact, I think it is best to consider a "contractarian" point of view. In brief, the reason I agree to donate my body to science is selfish and societally driven. If another person dies, and their body can benefit me if it goes to scientific research, this is good for me. I like it when other people agree to donate their bodies to science! So I pressure them to do so. In return, I submit to the pressure that they levy on me to benefit their lives. I hope, in the bargain, that enough people die before I do to prolong myself. And so we sign what is, in a sense, a social contract to donate our bodies to science. What the hell does this have to do with climate science (and a host of other topics)? Consider the possibility that organ donation is a known science, but there is some reason that we will never experience the positive outcome of anyone livings organs. For example, suppose there was some scientific reason that organs, once obtained from a dead body, must wait in seclusion for 100 years before they matter to me. Encouraging other people to donate their organs won't benefit me, I'll never reap the rewards. If people in the past donated their organs, this is also no encouragement for selfish me to donate my organs upon death, because I can't enroll myself in a mutually beneficial social contract. It would seem in this framework that organ donation would die out as a practice.

This is extremely strongly evidenced in climate change mitigation. We have no real method of having our actions altering the climate we will experience, and it is therefore hard to engage in a social (or real) contract in which parties will agree to limit their emissions, even when there is clear evidence that doing so is necessary to limit the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions. It seems the contractarians have it. There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics. - Mark Twain People are more likely to answer factual questions incorrectly if the facts do not conform to their political biases, even if presented with news stories disconfirming their preferred belief. With money on the line, however, they will. The consequences for climate policy here are rather broad. Wonkblog writes up the a reading of a recent paper by Larry Bartels at Princeton, who showed that Democrats were: Much less likely than Republicans to correctly answer questions about whether inflation went down under President Ronald Reagan (it did) and whether unemployment also fell (it did): A second group of researchers found: Republicans presented with news articles pointing out that there were no WMDs in Iraq were more likely to say that such weapons were found than Republicans who didn’t read those articles. The implication here is that people with strong political beliefs are willing to register their political belief in a survey even at the expense of disconfirming an actual fact, which recalls the beautiful quote by Twain (which he claimed originated in Benjamin Disraeli) Yet when told that incorrect answers would be penalized by monetary fine, and by including the category "I Don't Know" as a response indicating a sort of "conscientious objection") the partisan gap (remember, this is the spread in answers on a fact based on political affiliation) dropped by 80%.  The two main takeaways here?

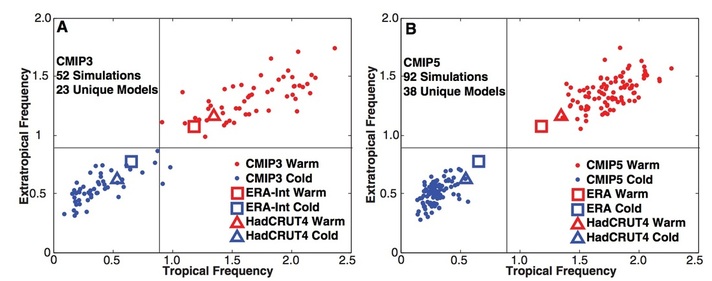

This calls into question reports on the acceptance of climate change in the United States: including the results from this Gallup poll. Gallup shows a major conservative bias towards a belief that climate change is exaggerated, and a liberal bias of similar magnitude (relative to the mean) towards a belief that it is not. Being that the "controversy" over climate change has become such a trenchant partisan issue, and that there is no magic information transmitted to Democrats that Republicans can't access, could it be that people are simply registering their political or religious belief into a survey, rather than their ignorance? The most interesting short paper I have read in the past few years is the pre-press article by mathematician Kyle Swanson: "Emerging selection bias in large-scale climate change simulations" (behind the Wiley paywall). In it, Swanson shows that the ensemble of models most popularly used for scientists exhibit a selection bias towards accurately capturing some phenomena (say the Arctic sea ice extent). In turn, this has resulted in (for other important phenomena) an intra-model spread which has decreased through the multi-year model refinement process, but whose mean has shifted further away from reality. In other words, there is a selection pressure on climate models which seems to be guiding them to converge upon the same result... in the words of evolutionary biology, researchers belief that they are "getting something right" is what is paying for these evolutionary changes. Yet according to Swanson (and a privately held belief of many other researchers) this satisfaction is misplaced. In the paper, Swanson retells Feynman's story of what happened after Robert Milikan miscalculated the charge on the electron. When they got a number that was too high above Millikan’s, they thought something must be wrong–and they would look for and find a reason why something might be wrong. When they got a number close to Millikan’s value they didn’t look so hard. And so they eliminated the numbers that were too far off, and did other things like that (Just to establish a baseline for this criticism, this selection bias is related to model-predicted or model-diagnosed patterns, and cannot be used to criticize climate change as a scientific fact. That the world is warming has been observed, evidenced analytically, and demonstrated in models over a wide range of complexities. Enough about that.)  The picture is a figure from his paper, showing how the model spread of the frequency of anomalously warm and cold months changes from the CMIP3 (~2007) and CMIP5 (~2010) intercomparison projects. This is plotted against "observations" from the reanalysis products HadCRUT and ER. The trend is obvious: the models tend to get cluster together but their mean does not shift towards the actual data. For a long time, the rub on climate models was that they had very low precision, model spreads were large and uncertainties were high. The unmentioned benefit for this was in accuracy: real data often fell within error bars of prediction. Now we have increased model precision at the expense of accuracy, and in the hierarchy of model outcomes, accuracy should be placed above precision. Better to be reasonably sure than to be confidently wrong. This is troubling: the implication being that modellers are providing a selection pressure for results which is (in a second sense) "unnatural", and climate models are becoming increasingly covariant (perhaps in response to "improvements" in physical parameterizations that are added to the entire ensemble), but are not becoming more skillfull. Not unlike the cartoon rabbit who puts his finger in the dike, only to see a new leak spring forth somewhere else, the rush to improve climate models in certain areas has resulted in even larger problem. |

AuthorOceanographer, Mathemagician, and Interested Party Archives

March 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed